UPFINA's Mission: The pursuit of truth in finance and economics to form an unbiased view of current events in order to understand human action, its causes and effects. Read about us and our mission here.

Reading Time: 5 minutes

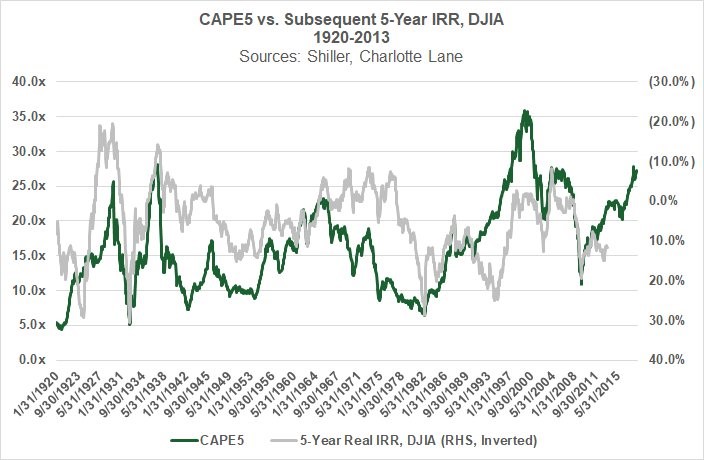

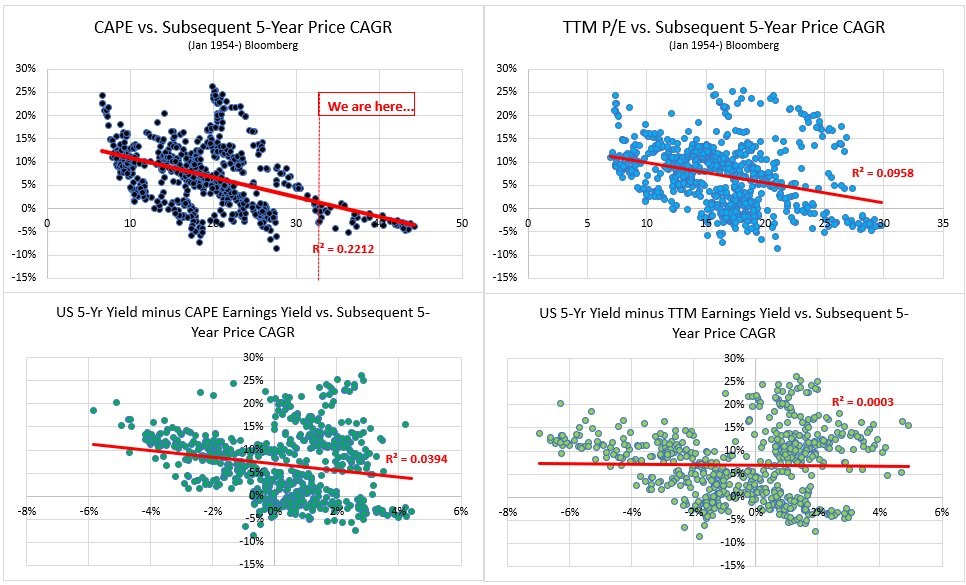

When investors first look at the CAPE ratio there is an incredible realization that it has a great track record of predicting long term returns. You can see the 5 year IRR versus the 5 year CAPE in the chart below. Since the S&P 500 10 year CAPE is at 33.35, which is very high, long term returns are projected to be very low.

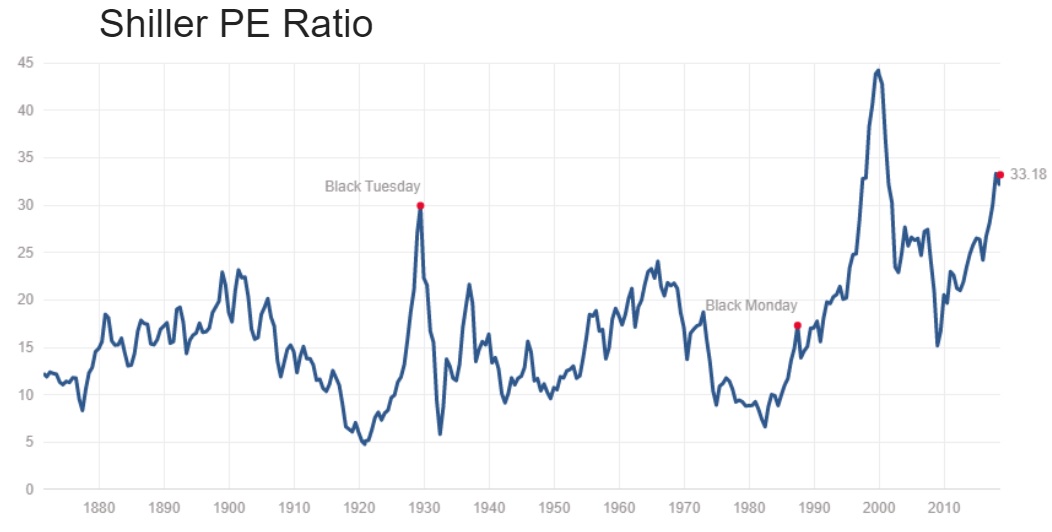

One obvious flaw in the CAPE ratio is that even though it uses data since the 1870s, there has only been one other market with such a high ratio which was the 1990s tech bubble. You can see the rareness of the current 5 year CAPE in the top left chart below. Using just one cycle to make an argument isn’t great and doesn’t stand the test of time.

Countering that point is that even though the CAPE ratio has rarely been this high, we can use the relationship between CAPE and returns to assume high rates equal low returns. The problem with that point is the CAPE ratio has been rising in the past few decades as stocks only shortly fell below the median CAPE ratio which started this current bull market which is the longest in history. The median ratio is 15.66. Stocks were below that valuation from November 2008 to April 2009. The worst recession since the Great Depression put valuations below the median for only 6 months.

Technically, followers of CAPE would say stocks should almost always be bought except when the CAPE ratio is very high like now. While that’s a fair point, the fact that the Shiller PE has been higher than its historical median for most of the past few decades seems to suggest there have been changing market dynamics which make it less relevant.

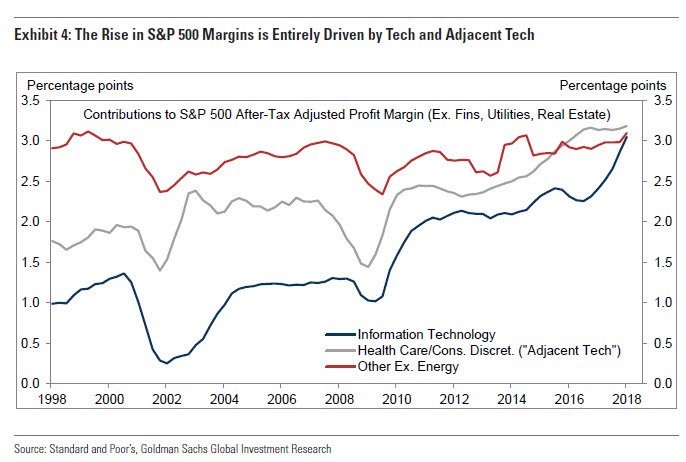

The biggest assumption CAPE makes is that margins will fall. There’s debate whether this is cyclical action or mean reversion. Either way, the current record margins are projected to decline. Investors fear when anyone says ‘this time is different’, but it’s fair to question if the high margins the tech sector has produced must fall just because margins in other industries did so in the past.

Every sector has different levels of competition and sizes of moats. For example, you wouldn’t expect a low margin business like grocery stores to suddenly experience an increase because it is below average. There is no mythical force which causes margins to rise and fall to meet an arbitrary perfect number (the mean).

In economics, we are taught in perfect competition all profit margins fall to zero. If you’re searching for a perfect number in theory, the answer is zero. Clearly that won’t occur for S&P 500 firms as competition isn’t perfect and historically margins have been positive. Even margins for individual products aren’t predictable. Many predicted that Apple would crater because previous consumer products saw pricing competition destroy margins. However, Apple has been able to raise prices on its iPhones. The iPhone is the most profitable product in human history.

The conclusion of this thesis is CAPE is predisposed to be bearish because it assumes margins will contract. There have been a few decades with a high CAPE, so it may be too bearish if you use the data going back until the 1870s to make a prediction. The chart above explains why we focused on tech margins so much in this discussion. As you can see, the rise in tech and adjacent tech firms’ margins are the reason margins are at record highs. Some CAPE followers believe they have a guaranteed reason to avoid stocks for the long term until they crash because of the high CAPE ratio, but understand that you are betting tech margins will fall closer to the average if you make this bet. It’s fine to be bearish on stocks if you think the cycle is near its end. This discussion is purely about being bearish on stocks because of valuations.

Tech’s Effect On Monetary Policy

In a Twitter exchange with Neel Kashkari in November of 2017, we asked Neel about the Amazon effect which is when its low prices suppress inflation. Neel discounted our point as he said he didn’t believe low inflation was driven by tech because productivity growth is low. He made a confusing point because clearly technological advancement and productivity growth aren’t the same thing. The internet is one of the biggest advancements in human history regardless of the government’s calculation of productivity growth. Secondly, there’s a big difference between Amazon causing low inflation and Amazon being the sole reason behind low inflation. Amazon is a factor, but obviously not the only one.

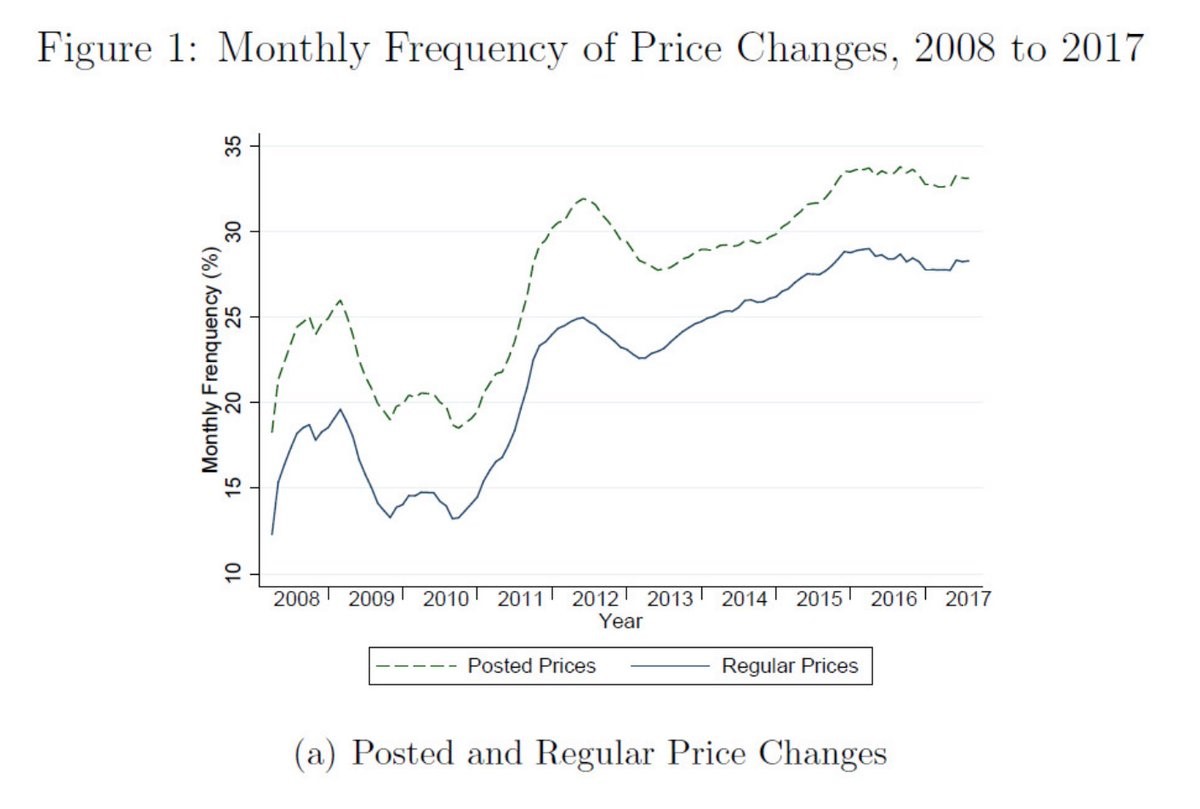

There was a new paper presented by Alberto Cavallo at the Kansas City Fed’s annual symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. It was related to online retail’s affect on prices, but it had new conclusions which could render the Fed’s interest rate policy a useless tool to affect markets. Prices are changing more rapidly as you can see in the chart below.

Amazon competing with retailers has caused them to change prices quicker. From 2008 to 2017, the average duration of prices of goods sold at large American retailers declined from 6.5 months to 3.7 months.

Cavallo’s paper stated:

“For monetary policy and those interested in inflation dynamics, the implication is that retail prices are becoming less ‘insulated’ from these common nationwide shocks. Fuel prices, exchange-rate fluctuations, or any other force affecting costs that may enter the pricing algorithms used by these firms are more likely to have a faster and larger impact on retail prices that in the past.”

As we mentioned, this new finding could make the Fed’s interest rate policy useless as algorithms determine prices. The mainstream understanding of monetary policy is sticky prices, or prices which aren’t affected by supply and demand instantly, give interest rates the power to bring supply and demand back into equilibrium. With instantaneous prices, the Fed will need to resort to different policies if it wants to affect markets. Surely, algorithmic prices at retailers won’t end inflation and unemployment, which the Fed seeks to control.

Cavallo’s paper stated:

“Labor costs, limited information, and even ’decision costs’ (related to inattention and the limited capacity to process data) will tend to disappear as more retailers use algorithms to make pricing decisions.”

There’s no question that online retail sales will grow as a percentage of total sales in the intermediate term. The fact that online pricing has caused traditional retailers to change prices quicker supports our claim that the difference between online and physical stores is dwindling. The pie won’t be separated in the future; all of retail will be different, transformed by technology.

Have comments? Join the conversation on Twitter.

Disclaimer: The content on this site is for general informational and entertainment purposes only and should not be construed as financial advice. You agree that any decision you make will be based upon an independent investigation by a certified professional. Please read full disclaimer and privacy policy before reading any of our content.