UPFINA's Mission: The pursuit of truth in finance and economics to form an unbiased view of current events in order to understand human action, its causes and effects. Read about us and our mission here.

Reading Time: 4 minutes

Too Big To Fail Definition

The definition of the term “too big to fail” refers to a company that poses negative systemic risk to the entire economy in the event of failure. Thus far no firm designated as too big to fail has failed, therefore this is a theory, one that you do not want to experiment with to determine its viability. While Lehman Brothers was allowed to fail by the Federal Reserve and the US Treasury in 2008, the bank itself was not large enough to cause prolonged negative systemic impact. The fact that Lehman Brothers was an investment bank, not a commercial bank, and did not have depositors, made it feasible for the government to allow the company to fail.

It becomes especially dangerous when the ‘too big to fail’ term is applied indiscriminately to any company that is large in size in various industries and countries since it implies that any large company that has an unsustainable business model should be supported by the tax payer. The most efficient and least costly method to manage failure of large firms is the bankruptcy laws which are already in place. By pledging tax payer funded government support to any company on the sole grounds that it is large and could potentially hurt the economy when it fails creates impassible economic inefficiencies as well as remarkable fiduciary and moral hazards that are akin to any government run organization in primarily Socialist countries. Moral hazard is when a firm’s incentives aren’t aligned to benefit shareholders (consumers, investors, vendors, etc). An example would be companies taking on excess leverage knowing that in the event of economic slowdown or disruptions to their business there will be a taxpayer funded financial support.

How Banks Got Too Big To Fail

It’s important to define that bailouts are funded by the taxpayer and not the government. The government is thought to be above the laws of mathematics, with many presuming it can spend unlimited amounts of money without recourse. This brings us to another term which is ‘too big to bail.’ It’s difficult to say what the limit on leverage is, but the limit on bailouts is what the taxpayer can afford. The government gets into an impossible to solve situation when a bank is too big to bail and too big to fail. This is intertwined with the leverage situation because if a bank has too much of it, fulfilling the bank’s obligations would be impossible for the government.

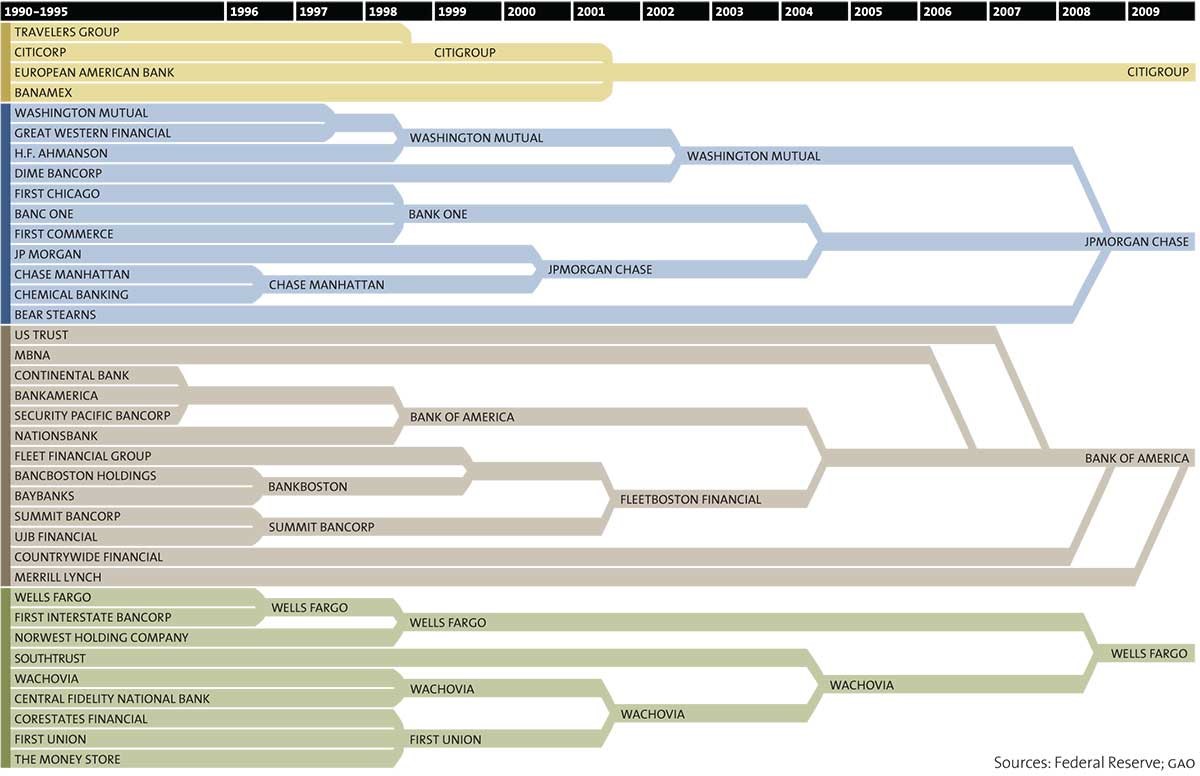

Even though financial regulations have been implemented to try to prevent the next crisis, the system may be more vulnerable than ever before. As we have detailed before, FDIC insurance for instance, creates more systemic risk not less as a direct result of moral hazard. Just like in the laws of physics, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. There are now only four major commercial banks: Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. There’s also only two major investment banks: Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. If you’re wondering how the US got to the point where there’s only four major banks, the chart below provides a detailed glimpse at the merger and acquisition activity over the past few decades.

The creation of the four mega banks is the result of free market acquisitions, regulations and government intervention. One example of a government managed one is the failure of Washington Mutual which happens to be the largest bank failure in US history. The U.S. Office of Thrift Supervision took control of Washington Mutual Bank and put in receivership with the FDIC. The FDIC than sold the bank subsidies to JP Morgan for $1.9 billion.

It’s arguable that the government is responsible for all the M&A activity which happened during the financial crisis because by lowering fed funds rate it spurred an increase in mortgage availability and demand, yet to subsequently raise fed funds rate which abruptly halted the upward ascent of house prices and caused a period of deleveraging from unsustainable loans that were provided during periods of low interest rates. While Bank of America bought Countrywide on its own accord, the reason Countrywide was in such poor place in the first place was because of the collapse of the housing market in the southwest.

To recap, there are now only four banks. While they may be in fine shape now given the massive liquidity injections by the Federal Reserve since the financial crisis, each one is bigger which means the risk posed to the economy in the even of one of them failing is much larger. While the situation of determining if a bank failure would collapse the system is theoretical when there are dozens of banks, when there’s four banks it becomes probable, not just possible.

Should Banks Be Too Big To Fail?

The pressing issue now is what to do with this situation. The two options are to either break up the banks or allow them to stay as they are with a guaranteed a bailout if they fail. If the government was afraid of bank failures in the past, the current situation implies that there’s no question that it would bail out one of the banks if they had problems. This situation is awful because it is expensive and creates a moral hazard since other banks would then anticipate a bailout as well, as was the case with Lehman Brothers. It’s arguably worse than socialism because the risks are socialized, but the gains are privatized. One way to describe this system is corporatism or cronyism. Having four banks creates infinite moral hazard. The banks can call the government’s bluff by taking large risk because they know they will be bailed out. In addition, this creates friction in the form of fines between the government and the banks. This friction ultimately affects not only depositors but also small businesses and consumers who rely on structurally sound banks to obtain loans, thus slowing down the growth of the economy.

As was mentioned, the other option is breaking up the banks. This is risky and difficult because it’s like unwinding a ball of yarn which is tangled. It’s tough to put the system back the way it would be if the government never got involved. Questions arise such as “how many banks should be created?” and “what parts of the banks should be sold off?” and “who should they be sold to?” While breaking up the banks is difficult and messy, it may be the only solution to the ‘too big to fail’ dilemma. As we have detailed previously, regulations have a proven track record of not preventing crises, so they can’t be relied upon.

Have comments? Join the conversation on Twitter.

Disclaimer: The content on this site is for general informational and entertainment purposes only and should not be construed as financial advice. You agree that any decision you make will be based upon an independent investigation by a certified professional. Please read full disclaimer and privacy policy before reading any of our content.