UPFINA's Mission: The pursuit of truth in finance and economics to form an unbiased view of current events in order to understand human action, its causes and effects. Read about us and our mission here.

Reading Time: 5 minutes

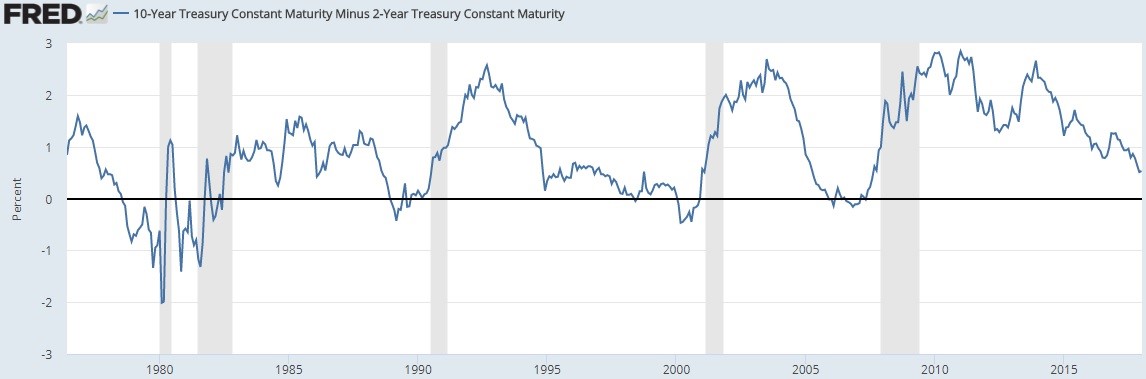

Although Yellen is a ‘lame duck’ central banker now that Jerome Powell was selected to take the helm in February, she’s still making headlines for unorthodox statements. As you should be well aware, the yield curve is one of the best recession warnings that exist, something we’ve discussed previously in detail. As you can see from the chart below, the yield curve has inverted before each recession since the 1970s.

The Yield Curve Has A Great Track Record Of Predicting Recessions

This is where Yellen’s statement comes into play. She shockingly brushed off the concept that the yield curve is important to setting policy. She said “correlation is not causation.” She’s correct that the yield curve inversion doesn’t cause a recession since there have been times when it has been wrong, but the high correlation makes it a trusted economic indicator. Ignoring the yield curve inversion would be like doing the exact same thing and expecting a different result, which is something Albert Einstein defined as the definition of insanity.

The point Yellen made was that a recession isn’t near. However, that point is illogical because the yield curve isn’t exactly saying a recession is near. The yield curve went inverted for the first time last cycle in December 2005. That was 2 years before the recession. Considering the fact that the yield curve isn’t inverted, a recession could be 3 years away. She’s building a straw man by claiming the yield curve is indicating a recession in the intermediate term.

Yellen Is Correct: The Fed Is Still Dovish

Let’s look at her point in more detail, she said, “When the yield curve has inverted historically, it meant that short-term rates were well above average expected short rates over the longer run. Typically, that means that monetary policy is restrictive, sometimes quite restrictive. It could more easily invert if the Fed were to even move to a slightly restrictive policy stance.” Her points all make sense, but it’s founded on a straw man argument.

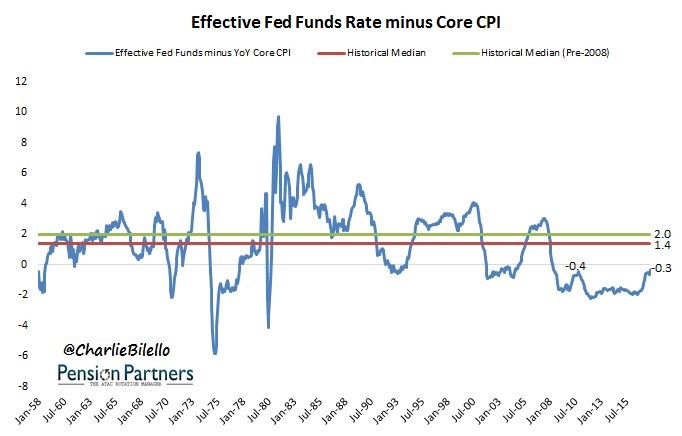

The chart below shows the Fed funds rate minus the core CPI. It gives us a rough idea if the Fed is hawkish or dovish.

The Fed Is Dovish As Of Early 2018

The Fed is currently on the dovish side. A couple more hikes would probably cause the Fed funds rate to jump ahead of the core CPI if inflation doesn’t increase much in the meantime. In context, the Fed funds rate has gotten over 2% higher than core inflation in many previous hike cycles. If core inflation stays at 1.8%, then the Fed funds rate would need to get to 3.8% for that to occur. The current expected Fed funds rate in 2020 is 3.125% meaning the Fed will be contractionary, but not as much as the end of prior cycles. This all supports her point, but it also agrees with the yield curve. She’s discounting the yield curve for an unknown reason.

It’s highly disconcerting to see the Fed dismiss the yield curve as it has a great track record. The Fed never wants there to be a recession. It would be happy to see the yield curve wasn’t inverted before the recession scare in 2016. It’s easy to see people’s biases when a metric changes its tune. For example, bearish investors complained about the lack of earnings growth in 2016, but now many conveniently ignore the great growth seen in 2017.

Yield Curve Is Expected To Flatten

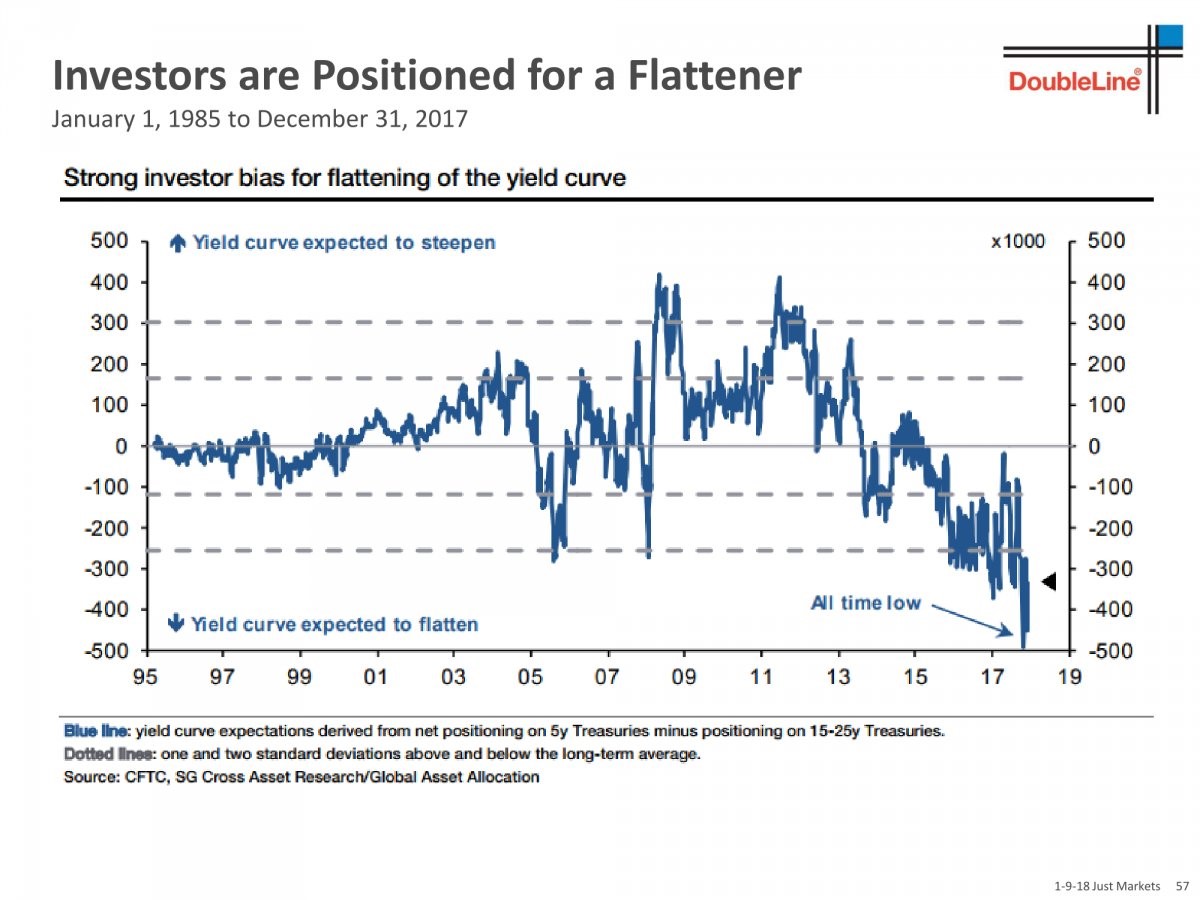

We have talked about the yield curve and expectations of hikes. Now let’s review the expectations for the yield curve. As you can see from the chart below, investors are more worried about the yield curve flattening further than ever before. There’s good reason to worry about the yield curve flattening because economic growth looks to be accelerating with the boost from the tax cut. This could spur inflation which usually ends business cycles. However, just because everyone thinks the yield curve will flatten, doesn’t mean it will occur right away. There could easily be counter-trend moves which put off the inversion for a few months.

Investors Expect A Flatter Yield Curve

QE Tightening Plays A Role

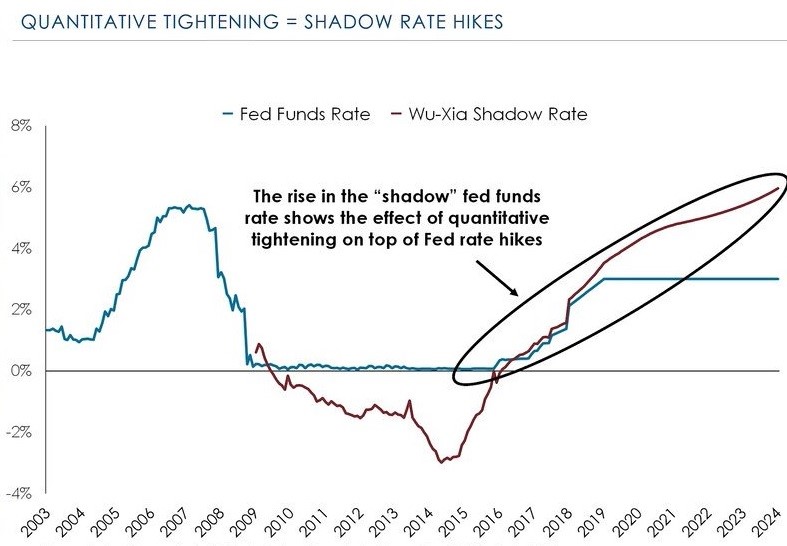

Shadow Rate Says Fed Will Be Hawkish Somewhere Between 2019-2020

One point we haven’t mentioned yet is where the Fed’s unwind program puts the hike cycle. The unwind is at $20 billion per month and will accelerate to $50 billion per month in the next few quarters. To contextualize the QE tightening with the Fed funds rate, we look to the shadow Fed funds rate. As you can see from the red line above, the shadow rate will be slightly higher than the Fed funds rate in 2018. In 2019, the gap widens. This means the Fed’s monetary policy will be getting more hawkish than Yellen would like to admit. The Fed wants to get the balance sheet to between $2 trillion and $2.5 trillion, but if the Fed is nearly as hawkish as it usually gets at the end of contractionary cycles, this goal probably won’t be reached.

Fed Running Out Of Time

By disagreeing with the yield curve, Yellen is expressing her fear that the Fed won’t be able to unwind the balance sheet by the amount it wants. The charts below estimate the Fed’s balance sheet size and reserve balances. As you can see, the unwind is expected to end in 2022. The Fed has gotten lucky that this expansion has been the 3rd longest since 1854. This would need to be the longest expansion by 3 years for the Fed to get to a balance sheet just below $2.5 trillion. The Fed is running out of time. This unrealistic schedule combined with Powell’s negative opinion on QE means the Fed might accelerate its balance sheet reduction in the next couple years.

The Fed Expects To Be Done With The Unwind In 2022

Conclusion

Janet Yellen will rue the day where she said the yield curve doesn’t matter if it accurately predicts another recession in a few years. To be fair, the questioning about the yield curve often implies it’s predicting a recession as soon as it inverts. Either way, Yellen’s term will end in a few weeks. It’s Powell’s decision if he wants the Fed to accelerate its unwind so it can meet its goal before the next recession. To be clear, if the Fed was to stop unwinding the balance sheet at between $3.5 trillion and $3 trillion, it wouldn’t necessarily be a disaster. The stock market would probably like that. The risk is Powell decides to ratchet up the unwind in the next couple years. He already doesn’t like the policy; the unattainability of the timeline might be enough for him to increase the size of the monthly unwind.

Have comments? Join the conversation on Twitter.

Disclaimer: The content on this site is for general informational and entertainment purposes only and should not be construed as financial advice. You agree that any decision you make will be based upon an independent investigation by a certified professional. Please read full disclaimer and privacy policy before reading any of our content.