UPFINA's Mission: The pursuit of truth in finance and economics to form an unbiased view of current events in order to understand human action, its causes and effects. Read about us and our mission here.

Reading Time: 5 minutes

The global financial system has produced remarkable situations in the past decade because of unprecedented central bank actions. We had another example of one as Japanese bonds sold off on Monday, July 23rd because investors were fearful of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) pairing back its stimulative monetary policy. In response to the market’s fear of the Bank of Japan’s July 31st meeting, the central bank offered to buy 10 year government bonds at a fixed rate of 0.11% to quell the sell off. This is remarkable because it shows the level of fear in the market in response to such a small change. The BOJ targeting the yield curve is so far from policy normalization, that it’s almost amusing, if it weren’t sad, to see such a reaction. The BOJ is trying to avoid a knee jerk reaction as it merely discusses how to mitigate the negative effects of accommodative monetary policy and mentions the possibility of slowly normalizing policy. This sparked a global move in government bonds as we will discuss in this article.

The Most Accomodative Central Bank

The Bank of Japan has rates at -0.1%, targets a 0% yield on the 10 year government bond, has guidelines to increase its balance sheet by 80 trillion yen per year, increases ETF holdings by 6 trillion yen per year, and increases REIT investments by 90 trillion yen per year. If the BOJ just discusses changes to its interest rate targeting and stock buying techniques, there shouldn’t be a market reaction, because that in itself is not contractionary. The BOJ wants to avoid the negative effects of its policies by not owning too much of stock indexes because this causes individual stocks to not properly react to corporate news and events, thus distorting asset valuations and not allowing the market to discover prices. As such, if companies are assured that their stock will always be bought by the BOJ through ETFs and indexes, this eliminates their incentive to perform well.

Japanese 10 Year Bond’s Reaction

As we mentioned, the 10 year Japanese bond had a big reaction in anticipation of the BOJ’s meeting. Its yield increased from 0.035% to 0.086% on Monday July 23rd. The Bloomberg chart below shows this is the highest level the 10 year yield has reached since February.

Source: Bloomberg

Markets usually are good at predicting actions by policy makers, but short term volatility is not always indicative of future trends. Don’t use this move to justify the thesis that the BOJ is about to unfold a normalization process in the next 2 weeks.

Inflation Set Up

Let’s contextualize the Japanese economy to help you understand the policy situation. Japanese inflation is weak since the year over year consumer price inflation was 0.7%, below the 0.8% estimate. Here is Japanese inflation dating back to 2013, shown in the chart below.

Source: Trading Economics

Core inflation, which doesn’t include food and energy, experienced a 1.2% decline over the past few years and was 0.8% year over year which was the highest rate since March. The inflation rate is below the 2% objective which indicates there won’t be hawkish monetary policy. The latest fiscal 2019 projection from the Japanese government is for 1.5% inflation including the October 2019 planned sales tax hike and 1% without it. The BOJ expects 1.8% core inflation. The private sector expectation is for only 1% core inflation. The government and the central bank will need to lower their forecasts instead of setting hawkish policy.

The 0.2% decline in Q1 GDP was likely a one off event, but it’s not like growth is expanding. Economists expect real GDP growth of 0.8% and nominal GDP growth of 1.8% in fiscal 2019 which starts in April 2019. The net percentage of businesses expecting an increase in output is 19%, according to Markit. This is the weakest reading from all the countries surveyed in the Business Outlook survey.

Slowing Bank Of Japan Asset Growth

The most hawkish part of the Bank of Japan’s policy is probably that the bank isn’t hitting its guideline for purchases of 80 trillion yen per year in government bonds. The FRED chart below shows the recent sharp deceleration in the year over year change in the central bank’s assets.

Source: FRED

In February 2014, year over year growth peaked at 47%. As of May 2018, it was only 8%. This is unlike the Fed’s balance sheet which is shrinking, but it’s still a major shift in policy. By the way, those predicting a collapse in equity markets because of slowing central bank purchases have been wrong. The year over year growth in assets from the major central banks has declined from about 25% in late 2016 to about 5% as of June 2018. That growth rate should turn negative in the next 12 months if policy goes as planned. Once it turns negative, that will be the real test for markets and asset prices.

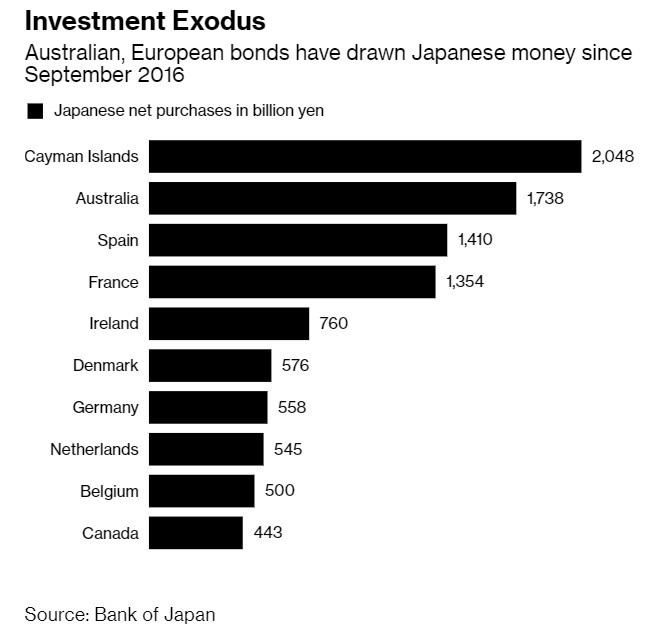

Bank Of Japan Causes Yield Suppression

The main reason we’re discussing the Bank of Japan’s policy is because its low rates cause Japanese investors to buy other countries’ bonds in search of higher yields. This suppresses global bond yields. Keep in mind, the yields aren’t directly related since there are hedging costs to remove the effects of currency volatility. The Bloomberg chart below shows the countries which have had the largest inflows from Japanese investors. This shows you which countries have had the largest yield suppression because of BOJ policies.

Source: Bloomberg

No More U.S. Curve Inversion

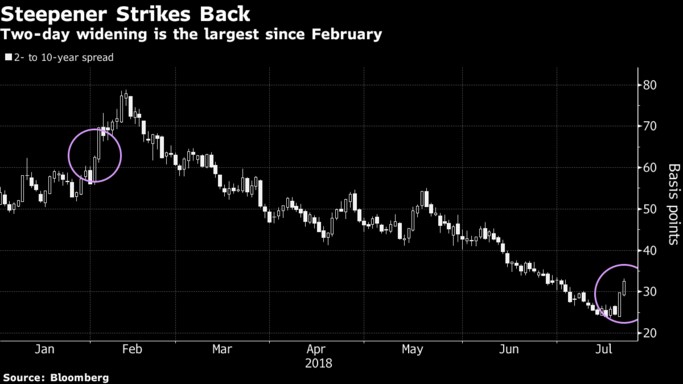

Perhaps the most important effect of a potential hawkish BOJ policy would be on the U.S. yield curve. The curve steepened on Friday and Monday as the 10 year yield rose about 12 basis points. The Bloomberg chart below shows the relentless flattening of the yield curve and the recent steepening.

Source: Bloomberg

Since BOJ policy doesn’t have much to do with U.S. growth or inflation, it supports the narrative that the yield curve doesn’t matter much this cycle because of central bank intervention. Maybe a yield curve inversion doesn’t matter because of central banks’ bond purchases.

Conclusion

The Bank of Japan is probably about to make modest tweaks in how it follows through on its dovish policy. There was a sharp reaction to this potential action in bond markets across the globe. This gives us an opportunity to review the BOJ’s policy and explain how the U.S. long bond yields could increase, which would flatten the curve, if the BOJ decides to normalize policy. It’s unreasonable to expect BOJ policy to cause or delay a U.S. recession, which makes investors question whether the yield curve is a good leading indicator this business cycle.

Have comments? Join the conversation on Twitter.

Disclaimer: The content on this site is for general informational and entertainment purposes only and should not be construed as financial advice. You agree that any decision you make will be based upon an independent investigation by a certified professional. Please read full disclaimer and privacy policy before reading any of our content.