UPFINA's Mission: The pursuit of truth in finance and economics to form an unbiased view of current events in order to understand human action, its causes and effects. Read about us and our mission here.

Reading Time: 4 minutes

The stock market correction was interesting because the coronavirus was a known risk before stocks started declining in late February. It started impacting China in late January. It seemed like the growth in Chinese cases was slowing, but surely it was never out of the realm of possibilities that it would impact other nations. Even an investor with little medical knowledge understood that. Why did stocks fall so sharply if people could have seen this risk ahead of time?

The answer is twofold. Firstly, all risks are known beforehand, but markets don’t trade solely off low risk events. It’s impossible to quantify what level the market prices in risks because we don’t know their exact outcome nor their odds of occurring. We can’t get in the heads of traders and figure out why they make certain decisions. There are always risks that don’t come to the forefront. It just happens that this risk did come forward. The second part of the answer is that stocks didn’t only fall because of the coronavirus. They fell because they were overvalued, because traders panicked as the selling got intense, and because of political risk.

Does The Coronavirus Matter?

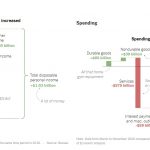

If you look at just 2020 earnings, the coronavirus probably should have sent stocks falling because the new base case from Goldman Sachs implies S&P 500 full year EPS will be $9 lower. Plus, the added uncertainty should lower the multiple. Contracting multiples and earnings is a toxic combination. Stocks react to earnings slowdowns which are almost always transitory. However, if you value stocks on all their future cash flows instead of just the next year, slowdowns shouldn’t impact stock valuations as much as they do. One aspect that pressures stocks when earnings slow is supply and demand as buybacks slow and sometimes firms issue new shares.

If you actually look at stocks based on their future profits instead of just next year, the coronavirus caused stocks to fall way too much. Make sure to expect stocks to overreact to temporary issues. We’re explaining how you can benefit from overreactions, not why they shouldn’t occur. It doesn’t matter if you think short term earnings volatility shouldn’t cause stocks to fall sharply because it always does. Recent earnings and intermediate term earnings forecasts are all investors have to go by. If you’re looking at individual companies, it’s very difficult (but not necessarily wrong) to hold through periods of weakness because you don’t know if the weakness is transitory. With the overall market, we have more confidence as earnings have always recovered (in America).

The Worst Case Scenario Doesn’t Justify This Decline

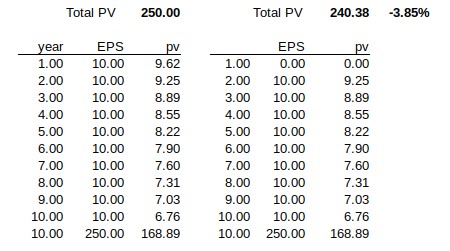

The table below from The Brooklyn Investor shows the discounted present value of future profits assuming the first year of profits is zero. As you can see from the top right corner, 1 year without earnings impacts the present value by 3.85%. That’s about a third of the decline stocks had. This is actually an unreasonably negative scenario because even in the Great Depression and the 2008 financial crisis, earnings never fell to 0.

With the Goldman Sachs new base case scenario, we were talking about 0% growth, not 0% earnings. If the coronavirus actually caused earnings to fall to zero, we’d see mass panic from investors. This is just an ultra-conservative exercise to review how a temporary blip has little impact on intrinsic value. Notice this example doesn’t include earnings growth either. If you’re curious let’s look at a more realistic, but still very negative example. If earnings in the first year fall 25%, the impact on the market’s intrinsic value is just 0.96%.

Valuations Caused Stocks To Fall

Valuations are a silent killer for stocks because they’re usually at least partially why stocks fall, but their impact isn’t obvious. There’s always a story that traders and the media make up. We like to say if stocks are expensive, it’s easier to knock them off their perch. That assigns blame to the negative catalyst, but recognizes the root cause of the problem (expensive valuations).

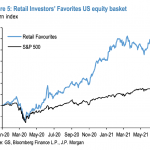

As you can see from the chart below, the S&P 500’s forward multiple quickly went from the highest in 8 years to near the long term average. If valuations helped cause the decline, then a V-shaped recovery is less likely. We could have a period with below average returns, starting at the peak in February, because stocks had too high a multiple.

We’ve already discussed the political risk, so we’ll give a brief summary. As the correction started, it looked like Sanders was the lone front runner. Recently the situation has shifted to where Biden is also a front runner. Stocks were reacting to headlines about the virus, but don’t assume traders were ignoring the election.

Low Yields Help (Might Be Temporary)

Low yields help valuations, especially for dividend paying stocks in the utilities and consumer staples sectors. Therefore, the decline in yields during this correction could support higher valuations. The S&P 500’s dividend yield is the highest relative to the 30 year yield since 2009. However, before stocks fully reflect the decline in yields, yields might increase. It’s probably a positive stock valuations aren’t juiced by low yields at the moment because the long bond in the short-term might be oversold.

As you can see from the chart below, the 10 year yield’s z-score of the past 126 trading days (6 months) is -4.1397 standard deviations below the mean.

In a normally distributed curve, 4 standard deviations account for 99.994%. Market returns aren’t normally distributed. That’s why this almost impossible pricing event has occurred. However, don’t let that minimize how overbought the 10 year bond is. The z-score is the lowest on record.

Conclusion

We think the coronavirus isn’t the only reason stocks corrected. Stocks were expensive, election risk increased, and traders panicked. A temporary impact to earnings, in which the next year’s earnings fall 25% and then recover, only causes a 0.96% impact to intrinsic value. Obviously, we know in the real world a 25% impact to earnings would cause stocks to fall well over 20%. That decline could be a buying opportunity if you know the impact is transitory. On another note, the long bond in the short-term might be overbought. If growth accelerates, following the negative impact of the coronavirus, yields should increase.

Have comments? Join the conversation on Twitter.

Disclaimer: The content on this site is for general informational and entertainment purposes only and should not be construed as financial advice. You agree that any decision you make will be based upon an independent investigation by a certified professional. Please read full disclaimer and privacy policy before reading any of our content.